On Balance: Using Retrospective Analysis to Increase Policy Learning in Europe

A retrospective exercise is an opportunity to learn and improve. With this in mind, an international consortium led by CSIL (Centre for Industrial Studies) recently developed an evaluation framework to carry out a retrospective assessment of infrastructure projects in several environmental sectors. The framework was developed as part of a study being carried out on behalf of the European Commission (Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy) to look retrospectively at 10 of the major infrastructural projects co-financed by the Commission over the period 2000 to 2013. While it will come as no surprise that, in retrospect, forecasts are imperfect, learning from mistakes or unexpected outcomes may improve the quality of forecasts. In turn, better forecasts may lead to better policy-making. This post reports some preliminary results from the study; more complete results will be presented at the Society for Benefit-Cost Analysis Conference in March 2019.

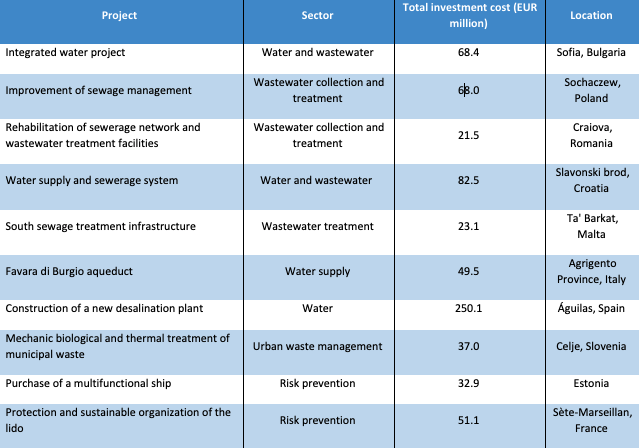

Just to give you a flavor of the study, the 10 projects are briefly presented in the table below. All the projects have been in operation for at least 5 years, placing—de facto–the assessment in an intermediate viewpoint when compared to the projected lifetime of the infrastructure (typically 20 to 30 years).

The original contribution of this framework is that it combines retrospective cost-benefit analysis with qualitative evaluation of the factors that can positively or negatively influence a project’s performance. The approach involved extensive field work and interaction with relevant stakeholders to collect data and information used to prepare the retrospective cost-benefit analysis. This information was also used to reconstruct the project history and to assess effects, such as certain environmental changes; such changes, although observable from an ex post perspective, are difficult to translate into monetary terms. The information also was used to identify the key drivers of observed project performance.

In fact, the objective of this ex post evaluation exercise was not limited to verifying the correctness of the ex ante cost-benefit analysis and/or discovering ex post deviations from the ex ante results. Rather the goal was also to analyze the long-term contribution of ten environment projects to economic development, quality of life, and well-being. For this reason, the methodology goes beyond a simple update of the ex ante cost-benefit analysis with observed data. Rather, the added value of this ex post evaluation exercise comes from performing a new cost-benefit analysis from today’s standpoint and understanding the reasons why some deviations occurred.

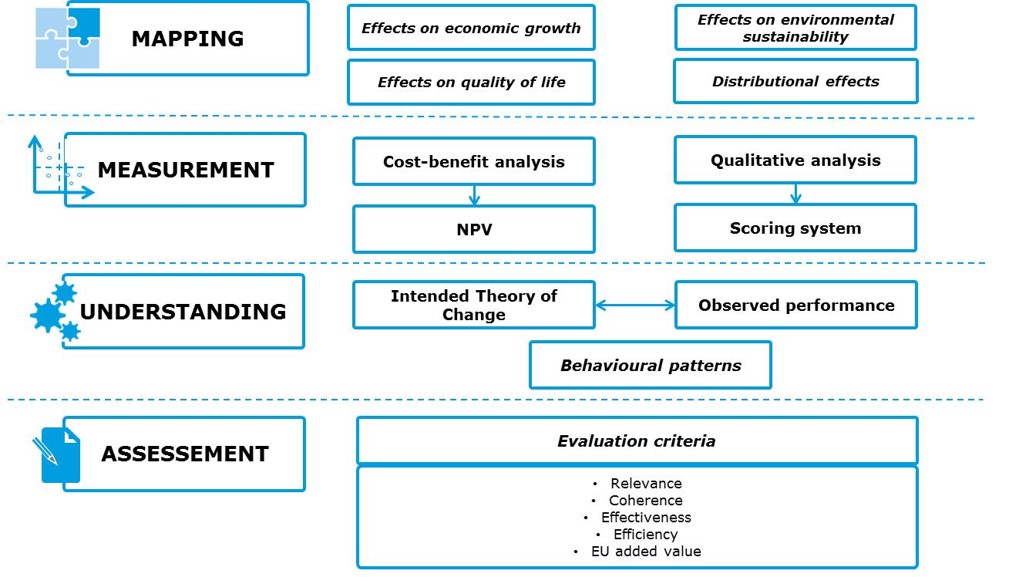

The study evaluation framework consists of four building blocks which are schematically presented in the figure below. This framework was consistently applied to the ten projects.

The first step involved mapping the various effects (benefits or costs) that environmental infrastructure projects can deliver. An extensive literature review provided the basis for developing a taxonomy of benefits expected to be generated by projects in different sectors.

The second step estimated project effects, including the magnitudes of costs and benefits, from an ex post perspective. The European Commission’s Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis of Investment Projects , which is the current reference for the appraisal of major infrastructure projects (ex ante), provided the starting point for the current analysis. However, the ex post perspective posed several challenges that required adjusting the approach in the Guide for the treatment of key elements, such as the definition of project boundaries, the appropriate reference scenario, and key parameters such as the social discount rate or shadow prices. As far as possible, effects were quantified and monetized. When this was not possible, effects were described and assessed qualitatively.

The third step focused on understanding project performance and the role that various factors, such as forecasting capacity and project design, played in determining project performance. Finally, the last step of the evaluation framework integrated all the findings into a narrative in order to assess each project according to the five evaluation criteria identified in the figure.

Our preliminary findings suggest mixed results in terms of effectiveness, i.e. the extent to which the expected effects were achieved. While the economic Net Present Value estimated ex post was positive for all projects, only a minority fully achieved their intended effects. In the integrated sectors (water and waste), the effectiveness of a project is often influenced by the timely implementation of complementary projects and measures.

In the large majority of cases, however, a project’s underperformance comes from assumptions used in project preparation. Environmental projects demand foresight, yet foresight is inevitably imperfect. Typically, because of optimism bias, benefits are emphasized while costs and completion time are underestimated. Even without such bias, forecasts are susceptible to errors. In the projects reviewed, forecasting errors often resulted from lack of experience. For example, some project planners failed to foresee the complexities associated with expropriation of property for building a wastewater network. In other cases, project promoters incurred forecast errors because of the limited capacity of the official statistical office to predict demographic trends.

What is the bottom line of these preliminary findings? Forecasting capacity is a critical aspect of project development and design that needs to be improved. Notably, this can be done through astute hindsight: learning from the past. Retrospection is a reflective (at times bittersweet) process of learning. In this regard, retrospective or intermediate cost-benefit analysis (when appropriately implemented and integrated with qualitative evidence) is a valuable tool for policy learning. If the systematic retrospective exercise is part of the project cycle and feeds into the decision-making process, the lessons learned can be used to improve the ex ante appraisal process by taking corrective action to counteract forecasting errors and spur result-oriented behavior.